For neuroscientist Sara Lazar, a form of meditation called open awareness is as fundamental to her day as breathing.

“I just become aware that I am aware, with no particular thing that I focus on,” explains Lazar, an associate researcher in the psychiatry department at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School. “This sort of practice helps me become more aware of the subtle thoughts and emotions that briefly flit by, that we usually ignore but are quite useful to tune into.”

But meditation doesn’t just change your perspective in the moment. Some studies show certain types of meditation offer an array of benefits, from easing chronic pain and stress and lowering high blood pressure to help relieve anxiety and depression. And, as Lazar’s research has shown, meditation can actually change the structure and connectivity of brain areas that help us cope with fear and anxiety.

“It’s become really clear that all of our experiences shape our brain in one way or another,” Lazar says. “A lot of people talk about meditation being a mental exercise. Just as you build your physical muscles, you can build your calm muscles. Meditation is a very effective way of training those muscles.”

What counts as meditation?

More than you might have believed. An intriguing if somewhat perplexing aspect of meditation is that it encompasses a broad range of practices. “It’s clear what is not meditation, but there’s less consensus on what it is,” Lazar says.

Open awareness, Lazar’s go-to meditation, joins other forms, including focused awareness, slow deep breathing, guided meditation, and mantra meditation, along with many variations. At their core, Lazar says, is an awareness of the moment, noticing what you’re experiencing and nonjudgmentally disengaging from intrusive thoughts that might interfere with your ability to attend to this task.

Meditation can also involve sitting with eyes closed and paying attention to your body and any sensations that are present. A regular meditation practice typically involves slowing down, breathing, and observing inner experience.

“Meditation can involve flickering candles, breath awareness, or mantras — all of these things,” Lazar says. “But there’s definitely an element of focusing and regulating your attention.”

A close look at how meditation alters the brain

Small MRI imaging studies have zeroed in meditation’s effects on the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep within the brain that processes fear and anxiety as well as other emotions.

Lazar and her colleagues have spent many years laying the groundwork to show how practicing mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) alters the amygdala after only about two months. The MBSR practice in this research consisted of weekly group meetings and daily home mindfulness practices, including sitting meditation and yoga.

What has their research found?

One key study involved 26 people with high levels of perceived stress. After an eight-week regimen of MBSR, brain scans showed the density of their amygdalae decreased, and these brain changes correlated to lower reported stress levels.

Building on this, Lazar and colleagues designed a study that focused on 26 people diagnosed with generalized anxiety, a disorder marked by excessive, ongoing, and often illogical anxiety levels. The researchers randomized participants to either practice MBSR or receive stress management education. These participants were compared to 26 healthy participants.

In this first-of-its-kind research, participants were shown a series of images with angry or neutral facial expressions while their brain activity was gauged using functional MRI imaging. At the beginning of the study, anxiety patients showed higher levels of amygdala activation in response to neutral faces than healthy participants. This suggests a stronger fear response to a nonthreatening situation.

But after eight weeks of MBSR, MRI imaging showed increased connections between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, a brain area crucial to emotional regulation. The amygdalae in participants with generalized anxiety no longer displayed a fear response to neutral faces. These participants also reported their symptoms had improved.

“It seems meditation helps to down-regulate the amygdala in response to things it perceives to be threatening,” Lazar says.

How can meditation benefits help us in daily life?

Lazar believes training your brain to stop and notice your thoughts in a slightly detached way can calm you amidst the muddle of work deadlines, family friction, or distressing news.

“That’s one of the biggest translations” of meditation to everyday benefits, she says. “The person or situation that is stressing you out won’t go away, but you can watch your reactivity to the situation in a mindful, detached way, which shifts your relationship to it.”

“It’s not indifference,” she adds. “It’s sort of like a bubble bursting — you realize you don’t need to keep going on this loop. Once you see that, it totally shifts your relationship to that reaction bubbling through your brain.”

Want to try meditation — or expand your practice?

Haven’t tried meditating? To get started, Lazar recommends the Three-Minute Breathing Space Meditation. This offers a quick taste of meditation, walking you through three pared-down but distinct steps. “It’s simple, fast, and anyone can do it,” she says.

Simple ways to expand this basic approach are:

- adding minutes, just as you might for exercise

- meditating outdoors

- pausing to notice how you feel after you meditate.

“Or try either doing a longer session or short hits throughout the day, such as a three-minute breathing break four to five times a day,” Lazar suggests.

Another way to enhance your practice is to use ordinary, repetitive moments throughout the day — such as reaching for a doorknob — as a cue to pause for five seconds and notice the sensation of your hand on the knob.

“As you walk from your office to your car, for instance, instead of thinking of all the things you have to do, you can be mindful while you’re walking,” Lazar says. “Feel the sunshine and the pavement under your feet. There are simple ways to work meditation into each day.”

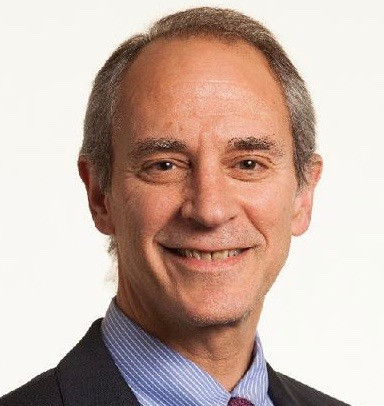

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

Maureen Salamon is executive editor of Harvard Women’s Health Watch. She began her career as a newspaper reporter and later covered health and medicine for a wide variety of websites, magazines, and hospitals. Her work has … See Full Bio View all posts by Maureen Salamon

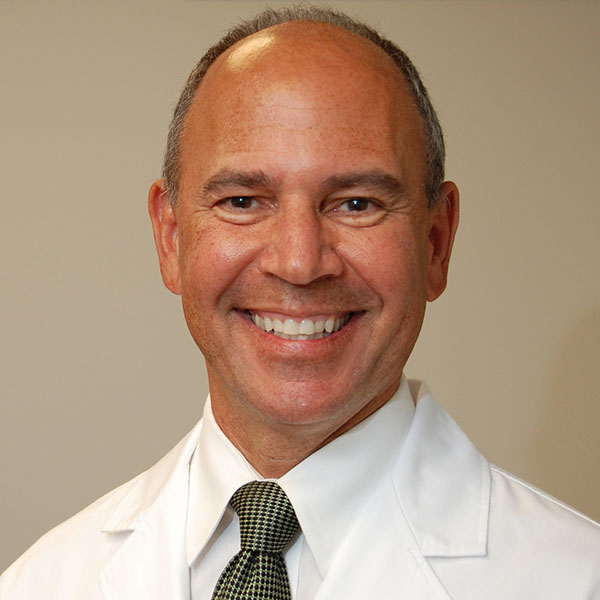

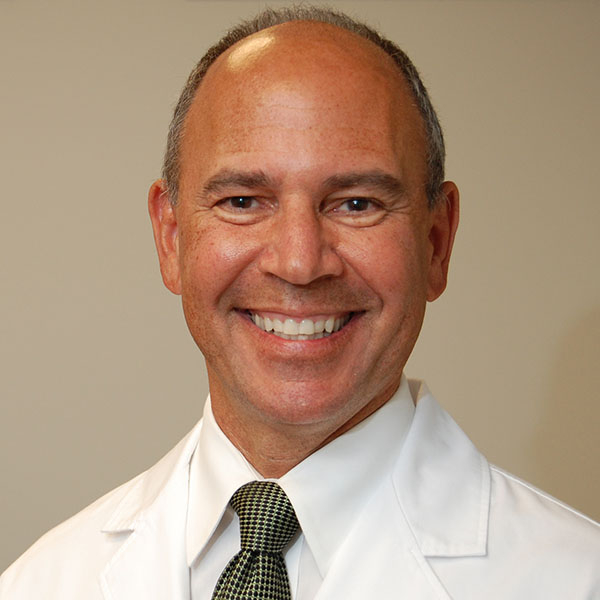

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD